Have you ever wondered whether there’s an optimal strategy for the card game Codenames?

This post details my quest to find a (near) optimal solution, which is technically within the rules.

Intro

I like the game Codenames. If you’re not familiar, head over to Wikipedia to learn more about the rules.

The strategy boils down to a few specific objectives:

- As the spymaster, give a word that is semantically linked to as many of your team’s cards as possible, while being semantically unrelated to your opponents cards. This word should also be especially unrelated to the assassin card.

- As a field operative (teammate), simulate objective 1, and then guess the cards the spymaster likely had in mind.

In practice, this isn’t easy at all, because it’s difficult to come up with a lot of words, and then evaluate how semantically close these are to all the words on the board.

Now, this game is called a “party card game”. This means the objective of the game is to have fun, and so ruthlessly optimising the strategy seems a little counter-intuitive, right? Right?

For those of us who consider finding exploitable loopholes “fun”, I thought I’d try find a near optimal solution, if possible to complete the game in a single turn, while obeying the rules.

An illegal strategy

If we want a way to communicate all our cards to our teammates, in a single turn, an immediate idea jumps to mind:

Just encode the positions of the cards somehow.

The cards are laid out in a grid, so you could possibly convey the location of the cards somehow. Possibly into the number clue - e.g. you could encode the positions 1 to 25 as 01-25, then just concatenate the locations of all your cards. i.e. you might give the clue: “blank: 050912181922”. Your teammates then just point at cards 5, 9, 12, 18, 19 and 22.

This works! But, the rules specifically say that the word you use as a clue must be related to the words on the cards:

Your clue must be about the meaning of the words.

And also:

The number you say after your clue can’t be used as a clue.

So, using the number is out. Looks like we’ll need to do something with the meaning of the words.

A technically legal strategy

Aside from humans, what else is good at finding semantic links between words?

Well, one of the interpretations of the latent space embeddings of language models are that these embeddings are semantic: the vector embedding of a word or phrase is semantically related to the vector embeddings of other words or phrases with similar semantics.

One of the widely circulated facts (from back in 2015!) which got me hooked on the concept of semantic embeddings was the idea that in some word embedding latent spaces, $king - man + woman \approx queen$ (you can read more here).

So, we could use these embeddings to find good words to use as clues. Perhaps these will even be perfect clues?

So, straight to the algorithm I’m proposing:

- Using any model capable of creating vector embeddings from text, the spymaster converts all words on the board to vectors, along with a dictionary of words.

- The spymaster finds the dictionary word which is closest in vector space to as many of their team’s words, and far from their opponent’s (and the assassin).

- The spymaster then calculates how many of their team’s words are closest to this chosen word (before encountering another word), and then says this word, and the number $n$.

- The field operatives use the same model to create vector embeddings of all words on the board, as well as the word the spymaster said, and then find the closest $n$ board words to the word the spymaster said.

A couple of notes:

- This algorithm doesn’t care what embedding you use, as long as it’s shared by both spymaster and teammates.

- The distance metric doesn’t matter either, as long as it’s shared 1.

- This is deterministic - there’s no risk that the spymaster and field operatives will arrive at a different list of $n$ words.

Now, does this work? Yes! (and it’s technically not cheating.)

Does it work perfectly? No! (at least I haven’t managed to make it work perfectly.)

As an example, for the following game, the suggested word is “penalty”. This would allow you to guess 7 of the 9 words on your first turn.

Our words are: [‘scorpion’, ‘orange’, ‘pyramid’, ‘carrot’, ‘plastic’, ‘missile’, ‘hole’, ‘crown’, ‘princess’]

Their words: [‘cloak’, ‘kiwi’, ‘cycle’, ‘bottle’, ‘fly’, ‘well’, ‘force’, ‘lion’, ‘litter’]

Assassin: [‘scientist’]

I’d challenge you to create a post-hoc rationalisation for what the semantic link is!

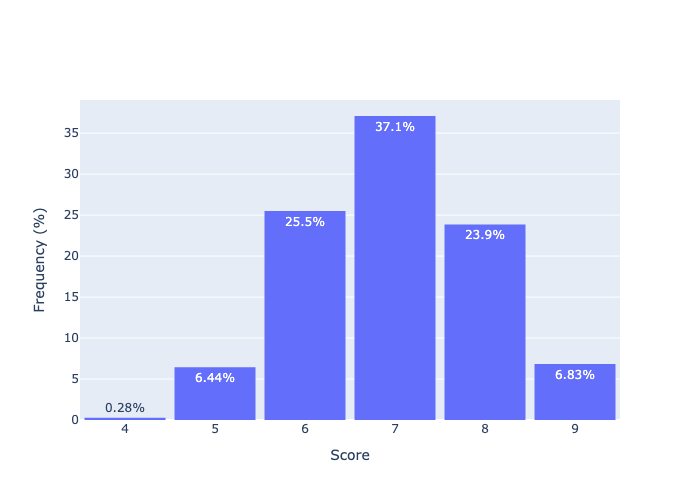

I then tested what the distribution of scores are using this (by playing the game 10000 times).

As you can see, we’re only able to win the game in a single turn around 7% of the time! The mode of the number of cards we can guess correctly on the first turn is 7.

You can have a look at the code I’ve written to simulate the game, using a few different embeddings here.

I had to do a little work to precalculate as much as possible, otherwise playing the games is quite slow. I could precalculate both the embeddings, and the distance matrix. All that needs to be computed on the fly is which word the spymaster should choose, to maximise the number of words their teammates would correctly guess, which is very quick.

After building this, I wondered whether other types of embedding would work. I doubted there was actually anything special about the fact that these embeddings are semantic (and if you look at the words that are suggested, you’d be challenged to create a post-hoc rationalisation for what the semantic link is).

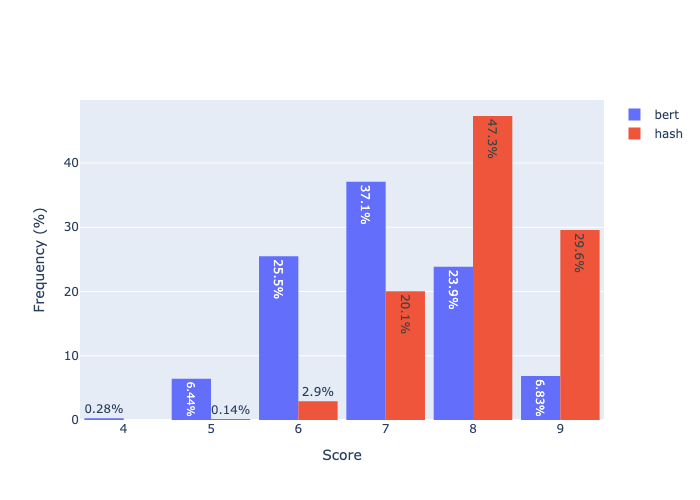

So, I hypothesise that any embedding which is well distributed (i.e. maps words to a broad range across the embedding space), should work well too. The fastest such embedding I could think of was a concatenation of cryptographic hash functions, which are designed to do good pseudorandom mappings.

My current version concatenates various versions of the BLAKE, MD5 and SHA algorithms, giving a 1904 dimensional embedding.

We can see here that the hashed version substantially outperforms the semantic version, giving a perfect clue about 30% of the time. Why might this be?

I don’t have a great answer, but I have some intuition for why this might be:

- The hashed vector is probably more uniformly distributed, so we get more efficient use of the words we have.

- We can have a higher dimensional vector, which also means that the embeddings can be more sparse, which means we’re more likely to find a useful embedded word.

A lower bound on the number of words required for an optimal solution

We only have around 70k dictionary words (many of which are obscure, or not-real-words). Can we calculate a lower bound on the number of words required in a dictionary to be able to play optimally?

Because the effect of the algorithm above is just to create a mapping between code words and dictionary words, we can think of the spymaster’s job as $f: w_d \rightarrow w_c$ and the field operative’s as $f^{-1}: w_c \rightarrow w_d$.

Given this, it’s clear that a perfect strategy needs a mapping to be 1 to 1 (in the sense that 1 dictionary word needs to map to precisely 1 set of 9 code words [of those displayed on the board]).

This doesn’t necessarily mean that each dictionary word needs to map to only one set of 9 words, but this would also give a perfect strategy.

So, we can give some first approximations of a lower bound on the number of dictionary words required.

We’ll do this by considering the number of combinations to encode the set of 9 code words.

A (really bad) first lower bound

One way to encode the set of 9 code words would just be a binary encoding: order the code words (e.g. alphabetically) and create a boolean vector corresponding to whether each word is in the set. This would be a binary number of length 400.

This has $2^{400}$ combinations, and so would require about $2.6 \times10^{120}$ dictionary words.

That’s a lot of words.

Obviously the vast majority of those combinations aren’t valid Codenames gameboards though (i.e. only those with exactly 9 ones).

A (slightly better) second lower bound

So, let’s only concern ourselves with the combinations of code words that we could see in a game.

Let’s count the number of combinations of 9 unique code words. This is just $400 \choose 9$, which evaluates to approximately $660 \times10^{15}$.

This is much smaller than the previous lower bound! But, it’s still much bigger than the 70k-ish words in my dictionary.

This raises the question - how much better could I expect my approach to work as I scale up the number of dictionary words?

Roughly how many would I need for a perfect algorithm?

The shape of third lower bound

I have a hunch that there’s a much better approach to represent the 9 words, than just finding all the combinations of 9 words and mapping them.

The idea is something like this:

- Find all the combination of $k$ words (where $k\ge9$) such that there exists at least one combination which exactly matches the correct 9 code words.

- Each time you add an extra word to the combinations, the number of combinations obviously increases, but you’re also able to cancel some others out.

- You only need to add an additional 17 words each time (25 - 17), so that there’s always one combination where the extra word doesn’t appear as one of the 25 cards which aren’t your 9.

- This feels like the Dobble problem/projective planes problem, but I haven’t yet managed to wrap my head around it. You can start here for a good description of this by Peter Collingridge. The Matt Parker’s Stand-up maths video is also excellent.

Wrapping up

I created a semantic word embedding based algorithm for playing Codenames, which plays better than a person, but still much worse than perfectly.

One ironic side effect of this is that if your opponent has access to a similar model, and you’re only able to guess 8 of the 9 words, then it’s likely that they’ll immediately win in their turn, since there are fewer of your words to “obstruct” their vector similarity.

Happy “cheating”!

Footnotes

-

It probably needs a bit more, like having a way to break ties, but I haven’t thought about this too much ↩